《贰点伍贰倍的玛德琳》——范诗磊个展

时间:2024/05/19——07/21

地点:深圳一树Arbre艺术空间

策展人:罗楚涵

如果我们设想,时间并非是一块密度均匀的玛德琳蛋糕——也就承认,时间与时间存在间隙。在这里,记忆是滑落间隙中的糖浆。它无固体形态、弥散在蛋糕体的任意角落,留下深深浅浅糖渍的痕迹。

正是这样的设想,使得我们可以谈论痕迹与触发记忆、返回特定时间之间的关系。苏格拉底将痕迹(tupos)称之为「记忆再现之物」(anamnesis),它常以视觉图象的样貌出现,统治着私人记忆。其另一层功能性要义是对集体记忆的再现。凝缩的图像是一座勾连四方的桥梁,成为时空下不相关之人的怀旧情绪仍能共通的原因与基本条件。

因此后来再次在别处瞥见隐约的糖渍痕迹时,便想起咬下第一口玛德琳蛋糕的滋味。我们从来无需证明为何蛋糕香甜,因为吃过的人就不会忘记。

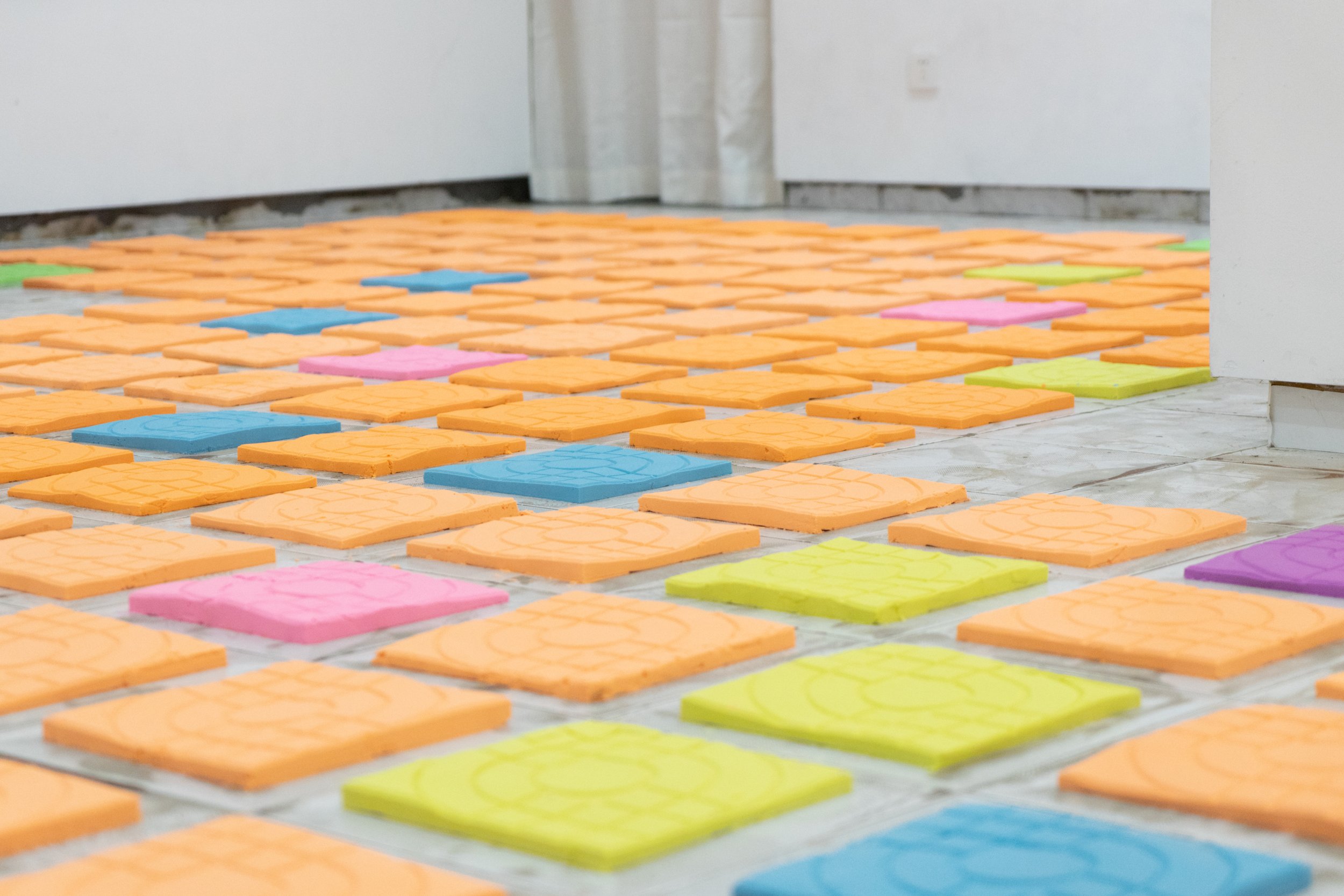

此次展览试图讲述的,正是这样一个关于记忆重现的故事,是从一块西班牙砖开始的。艺术家将这幅缠绵于一代人步行路上的图案不加掩饰地呈现于展厅,绒毛般「黄金年代」委身于个人的怀念中,被统摄在环状与网格结合的图案里。图像如何拥有一段人类的记忆?又或者,图像如何帮助我们重新在记忆中找到了记忆?而又是什么帮助我们确定了它的可读性?

当「西班牙砖」一出现,便调动起我们共同的思维活动,充当起对话的载体。任何一个需要观察它的观众都需得先破坏它本来面貌,继而去到空间中找寻新的佐证。在新旧闪回之间我们拿着返回好时光的钥匙:那或许在普遍的怀旧以外,更预言着再度重相逢的安慰。

If we envisage that time is not a Madeleine cake of uniform density - which confesses that a gap stays between time and time where memory is the syrup that slips through the gap. No solid form, leaving traces of deep and light sugary stains.

That gives us a basis to talk about the relationship between traces and triggering of memories and returning to a specific time. Socrates calls tupos 'anamnesis', which often takes the form of visual images that rule private memory. Another layer of its functionality is the reproduction of collective memory, when the condensed image becomes a bridge connecting every aspect, becoming the essential reason and condition for the common nostalgia of unconnected people.

Therefore, when we glimpsed the faint traces of sugar stains elsewhere, we remembered the sweet taste of the first bite of a Madeleine cake. We never have to prove the sweetness of it, because those who eat it will never forget it.

This exhibition tries to tell a story about the reappearance of memory, starting with a Spanish brick. The artist presents this pattern, which has dominated the walking paths of a generation, unabashedly in the exhibition. A plush golden age and nostalgia mind has been captured in a pattern that combines a ring and a grid. How does an image possess a piece of human memory? Or, how does an image help us to revisit a memory within a memory? And what helps us gain certitude of its readability?

When the Spanish Brick appears, it mobilises our shared thinking as a carrier for dialogue. Anyone who needs to observe it will have to destroy it first, thus a new evidence may emerge. Between the flashbacks, we hold the key to the good old days, which perhaps predicts a reunited comfort beyond the general nostalgia.

六次痕迹练习

6 practices of tupos

沿着作品对痕迹与记忆之间表征关系的讨论,在填平逻辑与顺序后,我们摘出六种意象,在虚构与非虚构交替的写作中,记录不同图像开始转变的瞬间。墙面上分散6块西班牙砖石膏,每一块由2000g的固体材料与520g的水制作而成,这也是展览标题的来源。从石像、忍冬纹、瓦尔堡、纹身、家庭相册再次回到西班牙砖,数字并不给出观看先后的提示。我们并非总按照时间线回忆过去,再面对相同的物象时,仍能一次次对其做出修改与解释。

In the exploration of the representational dynamics between traces and memories within the artwork's discourse, a structured logic and order are meticulously filled in. Consequently, six distinct types of imagery emerge, capturing the pivotal moments when these various images undergo transformation. Presented in alternating fictional and non-fictional writings, these depictions are symbolically recorded. Adorning the wall are six Spanish brick plaster pieces, each crafted from 2,000 grams of solid material mixed with 520 grams of water, thus inspiring the title of the exhibition. The sequence of viewing is not explicitly indicated by the figures, leading us on a journey from stone statues to Lonicera, from Warburg to tattoos, from family albums, and back to the Spanish bricks. Memories, however, are not always bound by linear chronology. Instead, upon encountering familiar objects anew, we find ourselves capable of continuously reshaping and interpreting them.

001 水中石象

Elephant in the Water

傍晚,她偶然看到诗歌中写有一汪泳池。泳池中一尊石作小象化作滑梯的形态,大雨冲刷、堆积的时候,象便隐于水中。她看不见象,如同象看不见她。那是在她另一个记忆里就存在的图景。几乎没有树林了,大象是巨物化做的愿景,从图画或者神话,以及永不可抵达的远方走来。尘土飞扬的集市中香料密布,熏住人的眼睛不好睁开。记忆本身都古老得不再识别自己,那可以被称作记忆消失的程式吗?——在一个逻辑尽头的死循环里。但象并未消解其中,它皱褶的皮肤被触摸,光滑的牙齿被珍藏。淋雨不损,沉沉地坠在大地上,直到变成一尊石像。而那其实就是她真正看见它的那天,隐于水中,只是她并不知道。

In the evening, she chanced upon a pool referenced in a poem. Within this pool, a diminutive stone elephant assumed the guise of a slide, its form gradually obscured by rainwater accumulating upon it. Unable to discern the elephant, she realized it couldn't perceive her either. It existed solely within her recollections, a fragment of her alternate memory. With forests now scarce, elephants were beheld as colossal apparitions, stemming from distant depictions in images, myths, and unreachable lands. The dusty bazaar brimmed with pungent spices, their aroma stinging her eyes and hindering vision. Memory itself, aged and weathered, seemed to elude recognition; could this phenomenon be construed as a manifestation of memory's erosion—a futile cycle culminating in logical impasse? Yet, the elephant remained impervious to dissolution; its wrinkled hide, a tactile testament, and its smooth tusks, a cherished relic. Unfazed by the rain, it descended into the earth, gradually petrifying into a stone statue. Unbeknownst to her, that was the very day she encountered it, concealed beneath the water's surface.

002 第58114窟

Cavern No.58114

忍冬,又名金银花,蔓性小灌木。最早的忍冬纹见于西汉末洛阳卜千秋墓壁画,因佛教东渐而逐渐被更为广泛地使用。严寒不凋、越冬不死的特质让它与佛教强调的「不死」与「轮回」精神相契合,被视觉化为一种自由波动的姿态。因此它繁荣于佛教文化最为兴盛的南北朝时期,在窟穴壁画边饰、人字披、龛楣和背光的位置频繁出现。

植物作为纹样渊源已久,是古希腊装饰艺术中重要的部分。我们在忍冬纹中不难注意到它与西方的棕榈、 莨苕叶、椰枣叶、葡萄叶之间的联系,而再追溯下去,棕榈叶纹样却是由古埃及象征太阳的莲花纹样发展而来。

图像到风格的建立并非只是艺术史的作用,李尔格(1858.1.14)为它提取出「艺术意志」——正如忍冬纹所体现的草原与海洋的不定期相遇,交通要塞的破除,以及语言对另一种语言的模仿。

Lonicera japonica, commonly known as honeysuckle, is a trailing shrub with a rich historical significance. The earliest depictions of the Lonicera pattern can be traced back to the mural paintings found in Bu Qianqiu's tomb in Luoyang, dating back to the end of the Western Han Dynasty. Its usage gradually expanded due to the spread of Buddhism towards the east. Its resilience against cold weather and ability to endure winter without withering aligns with the Buddhist ideals of "immortality" and "reincarnation," leading to its symbolic representation as a symbol of free-flowing gesture. Consequently, it thrived during the Northern and Southern Dynasties, a period marked by the zenith of Buddhist culture, where it frequently adorned the borders of cave paintings, friezes, niches, and cave backlighting.

Plants have held a significant presence as motifs in decorative arts throughout ancient Greece's history. Notably, the Lonicera pattern bears resemblance to motifs such as the Western palm, scopoleta, date palm, and grape leaves. The palm leaf pattern, in turn, originated from the lotus pattern of Ancient Egypt, which symbolized the sun.

The establishment of the Lonicera pattern as a stylistic element transcends mere art history; it embodies an artistic will, as articulated by Alois Riegl (1858/01/14). This includes the irregular juxtaposition of the steppe and the sea, the crumbling fortresses, and the imitation of one language by another, all of which are exemplified in the intricate beauty of the Lonicera pattern.

003 《记忆女神图集》

Mnemosyne Atlas

「它并未直接记载文艺复兴时期的艺术史,而是追踪了古典符号在空间和时间上的迁移,描绘了它们在这个过程中所经历的功能和意义的变化…」

图集是19世纪阅读范围最广的艺术史出版物之一。案牍术与摄影使得古典符号在时间与空间中自由移动,不断地形成、重组新的密语。瓦尔堡在《记忆女神图集》中所寄送的,与试图召唤「文艺复兴」的同时代艺术史学家一样,相信图像不只有被观看的命运,更有重启历史的力量。

"It does not merely chronicle the history of Renaissance art, but rather traces the migration of classical symbols across both space and time. In doing so, it charts the evolution of these symbols' function and meaning throughout their journey..."

The Atlas stands as one of the most widely acclaimed art history publications of the 19th century. Through meticulous casework and photography, classical symbols were afforded the freedom to traverse through temporal and spatial realms, perpetually configuring and reconfiguring new mnemonic patterns. Much like his contemporaneous art historians who endeavored to summon the essence of the 'Renaissance', Warburg’s contribution to the Atlas of the Mnemosyne Atlas embodies a profound belief in the inherent power of images. They are not merely passive objects to be observed, but potent instruments capable of unlocking and revitalizing history itself.

004 - .- - --- ---

... .... . / -.. .. -.. -. .----. - / .-.. . - / - .... . / - .- - --- --- / ... .--. . .- -.- / ..-. --- .-. / .- -. -.-- - .... .. -. --.

005 (假)相册

Pseudo Albums

她读道:

「我们还是不要抱怨过去吧!」

合页睡眠

细密的皱纹长满口腔

让一让

(你好,吻你,呼喊你)

藏在风里,藏在消音电话中,藏在时代的灰尘外

(在哪?几时?等我吗?)

那么大展宏图——

在矩阵棋盘格里,要玩的不是这种游戏

九月的照片还在

泳池浮在头顶

云朵,蓝天,干燥剂

没有辫子的人

成为母亲

最高温度37度,最低温度24度

降雨,降雨吗?

一小时而已。

细细挑选一段丝线

缝住嘴巴

那时如这时一样

跑的越快,就越觉得始终追不上

她那身鲜红的夹克便如血绸后缀

从傍晚的队伍里落单为夕阳

006 西班牙砖

Spanish Brick

「西班牙砖」并不来自于西班牙,它是90年代一种常见的中式旧城区人行道砖。雨天的路上,它们会潜伏为地雷,让不注意的人们弄脏裤子。西班牙以其建筑闻名,巴塞罗那也确有名为「巴塞罗那之花」 (flor de Barcelona)的地砖,成为城市文明的明信片。命名上近乎平移的挪用不难显现出旧时对远方审美的崇拜,而它在新的语境中自成一派,宛如一块视网膜上的空隙,难以忽视,因此也浮现出独特的美感。

The term "Spanish Brick" may be misleading, as it does not originate from Spain; rather, it refers to a common type of pavement tile found in Chinese old towns dating back to the 1990s. During rainy days, these tiles posed a hazard, often catching unsuspecting pedestrians off guard and leading to accidental soiling of trousers. While Spain is renowned for its architectural marvels, such as the famed "flor de Barcelona" (flower of Barcelona) tiles, which have become emblematic of the city's urban landscape. The appropriation of the name "Spanish Brick" is almost whimsically translational. This borrowing underscores a reverence for distant aesthetics, now entrenched within a new context, akin to a persistent anomaly in the retina that demands attention, ultimately emerging as a uniquely captivating feature.